Christopher Armitage || A general strike represents the most powerful tool available to working people. When enough workers simultaneously refuse to work, the entire economic system stops. No amount of political lobbying, no single protest march, and no electoral strategy can match the immediate pressure created when labor withdrawal halts production and commerce. Strikes force those in power to negotiate because the alternative becomes economic collapse. This power exists regardless of which party controls government, which judges sit on courts, or which billionaires own media companies. The strike threatens the one thing that matters most to those at the top: their ability to extract profit from other people’s labor.

The historical record proves this works. Iceland’s 1975 women’s strike saw 90 percent participation and forced immediate policy changes on equal pay. South Korea’s general strikes in 1996 and 1997 involved millions of workers and successfully beat back anti-labor legislation. The 2019 Indian general strike brought over 200 million people into the streets and workplaces, making it the largest strike in human history. France has used recurring general strikes for decades to defend pensions, labor rights, and public services. These weren’t spontaneous eruptions. They happened because organizers spent months and years doing the unglamorous work of education and recruitment, building participant lists until the numbers made action possible.

The Existentialist Republic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

But knowing strikes work means nothing if we cannot organize one. The gap between theoretical support and actual participation remains enormous. Most people sympathize with the idea of a general strike while simultaneously believing it cannot happen, that someone else will organize it, or that their individual participation won’t matter. Closing this gap requires direct person-to-person organizing. It requires asking people to commit, recording those commitments, and building a database large enough that a strike call becomes credible. Right now, that organizing work remains incomplete. We need people willing to go into public spaces, start conversations, educate their neighbors, and build the lists that make a general strike possible.

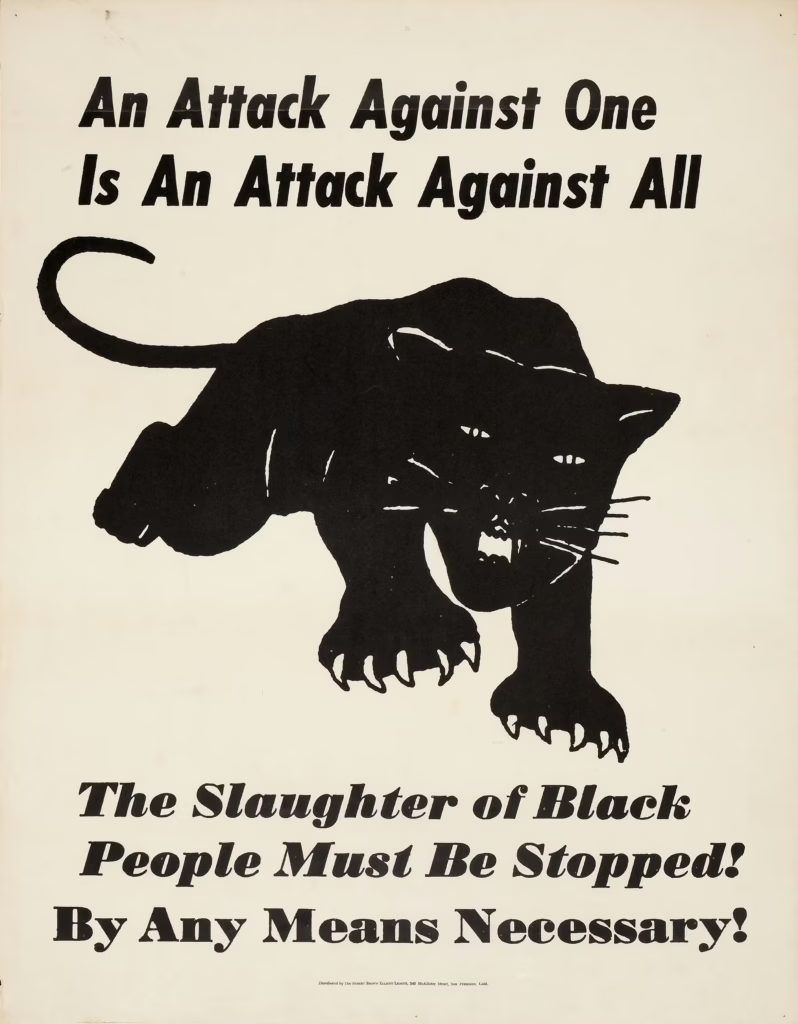

The Black Panthers understood how to combine immediate material support with political education and recruitment. Their survival programs, most famously the Free Breakfast for Children Program, fed tens of thousands of kids in cities across America starting in 1969. These weren’t charity operations. The programs served practical needs while creating spaces where organizers could talk with community members about power, rights, and collective action. Parents who came for breakfast learned about police brutality, tenant rights, and workplace organizing. Many became members or supporters. The programs built trust and demonstrated that organizing could deliver tangible benefits, not just rhetoric.

Free health clinics operated on the same principle. The Panthers provided medical care in communities abandoned by the health system while educating patients about preventive health, sickle cell anemia screening, and the political economy of healthcare access. People receiving services understood they were participating in something larger than individual charity. They were part of a movement building alternative institutions and challenging existing power structures.

This model worked because it met people where they were, addressed immediate needs, and created relationships that could support more confrontational organizing later.

Other movements have used similar approaches. Food Not Bombs chapters have been serving free meals in public spaces since 1980 while conducting political education and supporting labor strikes. The organization now has over 500 chapters in the United States. Industrial Workers of the World organizers in the early 1900s set up soapboxes in public squares, distributed literature, and directly recruited workers into the union through constant street presence. Korean labor organizers in the 1990s established information tables at markets and transit stations, explaining strike goals and why individual participation mattered. The pattern repeats: go where people are, offer something of value, and use that opening to educate and recruit.

For general strike organizing, this means establishing regular presence in high-traffic public spaces. Set up a table with hot beverages and hand warmers during cold weather. Offer hot chocolate, coffee, or tea for free. This creates a non-confrontational reason for people to stop and talk. Most people will take a cup and keep walking. Some will pause. A few will ask questions. Those conversations are where organizing happens. Have simple flyers explaining what a general strike is, why it matters, and how people can commit to participating. The flyer should be readable in 30 seconds and include clear next steps.

The conversation itself should be direct. Explain that a general strike means workers across all industries stopping work simultaneously to demand change. Describe the power this creates. Reference historical examples. Then ask the big question: will you participate if we reach the numbers needed? Not “would you support this” but “will you do it.” This distinction matters enormously. Passive support means nothing. Commitment to action builds the strike.

For those who express interest, direct them to generalstrikeus.com where they can sign a strike card. The General Strike US maintains a database of participants committed to striking once 11 million signatures are reached. That number represents approximately 3.5 percent of the U.S. population, a threshold research suggests can create successful mass movements. The visible counter on their website shows progress toward this goal, making abstract organizing concrete. When people sign, they commit to striking when called and provide contact information so organizers can coordinate action.

This street outreach requires sustained presence. One afternoon accomplishes little. Weekly presence in the same location for months builds recognition. People see you’re serious, that this isn’t performative activism. Transit hubs work well because of volume and because workers pass through during commutes. Areas outside large employers during shift changes offer access to concentrated groups of workers. College campuses, public markets, and community events provide other opportunities. The key is consistency and volume. Talk to hundreds of people. Most conversations will be brief. Many people will decline. The goal is finding those ready to commit and adding them to the database.

If religious zealots can go door to door proselytizing for their God, then why can’t we do the same for workers rights and anti-authoritarian protest?

Workshops serve a different function than street outreach. While street presence reaches people briefly, workshops allow deeper education and community building. A two-hour workshop can cover why strikes work, address common objections about risk and feasibility, discuss historical examples in detail, and create space for questions. The workshop format lets participants meet others considering the same commitment, reducing isolation and building collective confidence.

Structure workshops to end with concrete action. After the educational content, pass around a sign-up sheet or direct people to sign the strike card on their phones immediately. The transition from learning to committing should feel natural, not pressured. Frame it as the logical next step for anyone who agrees with the analysis. Provide resources for participants who want to organize their own workshops or street outreach. Give them the tools to become recruiters themselves, multiplying organizing capacity.

Workshop content should address the specific fears that stop people from committing. Many workers worry about losing their jobs. Explain legal protections for strike activity, acknowledge real risks honestly, and emphasize that mass participation reduces individual risk. When thousands strike together, retaliation becomes difficult. Others think strikes only work if everyone participates simultaneously. Explain that historical general strikes built participation over time through exactly this kind of organizing. Still others believe strikes are too radical or extreme. Counter this by discussing how concentrated wealth and political dysfunction leave few other options for forcing change in the public interest.

Local libraries, community centers, union halls, and places of worship often provide free meeting space. Start small with five or ten people and word of mouth. Announce workshops through social media, flyers at the locations where you do street outreach, and by directly inviting people you’ve spoken with. Record attendance and follow up with participants, asking them to recruit friends and family. Every person who signs the strike card represents one more participant. Every person who commits to recruiting others multiplies that impact.

If you attend No Kings Day protests or other mass gatherings, treat them as recruitment opportunities. Bring flyers and clipboards. Talk to people around you about the strike card. Mass events concentrate people already engaged in political action, making them efficient spaces for this organizing. The energy of large protests can help overcome individual hesitation about committing to strikes.

The organizing work described here requires time and persistence. It means having the same conversation hundreds of times. It means standing in the cold handing out flyers and hot chocolate to people who mostly ignore you. It means setting up workshops that only a few people attend initially. This work is neither glamorous nor immediately rewarding. But every successful mass strike in history depended on people willing to do exactly this labor. The Iceland strike happened because organizers went to every workplace and community group for months beforehand, asking for commitments. The Korean strikes succeeded because of information tables and teach-ins that built broad understanding of the issues. The Indian strike mobilized hundreds of millions because local organizing committees did door-to-door outreach.

We need that same infrastructure now. The database at generalstrikeus.com provides the national coordination point, but reaching 11 million participants requires thousands of people doing local organizing. It requires you going to your transit station with snacks and enthusiasm, heck maybe make some music while you’re at it because that gives you more ways to connect with people. It requires you hosting a workshop in your community. It requires you asking your neighbors, coworkers, and friends whether they will strike, then making sure they sign the card.

Fact is, we can either we build the lists and create the capacity for a general strike, or we watch as conditions continue deteriorating without the power to force change. Strikes work. History proves it. But they only happen when organizers do the work. Start this week. Set up somewhere public. Make the flyers. Have the conversations. Build the list. Every signature moves us closer to the numbers that make a general strike possible. Every person you recruit becomes another organizer spreading the message. This is how movements grow from ideas into material forces that change society. Go do the work.

If you found this article useful, check out my book “Conservatism: America’s Empathy Disorder,” which explores the psychological and neurological roots of how a political movement can abandon democratic principles in favor of power.

References

1996–1997 strikes in South Korea. (2025, March 26). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1996–1997_strikes_in_South_Korea

2019 Indian general strike. (2025, May 12). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2019_Indian_general_strike

Black Panther Party’s Free Breakfast Program (1969-1980). (2010, February 11). BlackPast. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/black-panther-partys-free-breakfast-program-1969-1980/

Chenoweth, E., & Stephan, M. J. (2011). Why civil resistance works: The strategic logic of nonviolent conflict. Columbia University Press.

Food Not Bombs. (2025). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Food_Not_Bombs

Food Not Bombs. (n.d.). Frequently asked questions. https://foodnotbombs.net/new_site/faq.php

Free Breakfast for Children. (2025). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_Breakfast_for_Children

General Strike US. (n.d.). The General Strike. https://generalstrikeus.com

Grevatt, M. (2019, January 14). All-India General Strike is largest in world history. Workers World. https://www.workers.org/2019/01/40392/

Harvard Kennedy School. (n.d.). The ‘3.5% rule’: How a small minority can change the world. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/carr/publications/35-rule-how-small-minority-can-change-world

Libcom.org. (n.d.). The Iceland women’s strike, 1975. https://libcom.org/article/iceland-womens-strike-1975

Robertson, D. (2016, February 25). The Black Panther Party and the Free Breakfast for Children Program. African American Intellectual History Society. https://www.aaihs.org/the-black-panther-party/

Swarthmore College Global Nonviolent Action Database. (n.d.). Icelandic women strike for economic and social equality, 1975. https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/icelandic-women-strike-economic-and-social-equality-1975

Swarthmore College Global Nonviolent Action Database. (n.d.). South Korean campaigners prevent government intention to weaken unions and facilitate lay-offs, 1997. https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/south-korean-campaigners-prevent-government-intention-weaken-unions-and-facilitate-lay-offs-

Discover more from Class Autonomy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.